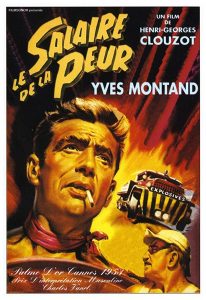

The Wages of Fear

Film Directed by Henri-Georges Clouzot; written by Henri-Georges Clouzot and Jérôme Géronimi from the novel by Georges Arnaud

I can think of three movies that focus early shots on insects. Blue Velvet has them crawling over that ear which sparks the events to follow. In The Wild Bunch, the outlaws come upon a group of children staging insect fights for entertainment. Here, in The Wages of Fear, our first vision is cockroaches tied together by a destitute child. David Lynch and Sam Peckinpah no doubt saw Clouzot’s masterpiece. Insects are a powerful metaphor, it turns out.

The moment those roaches appeared on that large screen in front of me (I was fortunate to first see this movie at the Carnegie Museum in Pittsburgh), I was entranced, anticipating the horror to come. I knew a little about the movie from blurbs, but was ignorant enough to expect things to go toward terror of a purely monster variety. Surely, someone would turn out to be a crook and this whole affair was going to end up noir. After all, it was made by a Frenchman in the Fifties.

I was an idiot. The movie is a study in unending existential fear- a feat which it accomplishes with drive and energy and passion. In retrospect, I can think of only one another filmmaker who has accomplished anything similar and that would be Steven Spielberg with Jaws and Schindler’s List. As a society, we have lived with Jaws as an artifact in our collective closet for so long that we forget how effective it truly is at generating morbid dread.

One appeal

of The Wages of Fear has been the straightforward nature of the plot. Like Richard Connell’s The Most Dangerous Game, the tale places men in an extreme situation and proceeds to question how people behave when stripped of the qualities that many of us take for granted. As opposed to Spielberg and others, Clouzot, Connell and Arnaud don’t leaven their stories with extraneous information. The characters may have motivations, but the hints are barely enough to grant them two dimensions.

In essence, we’re dealing with parables for a certain view of life. The appeal of the parable lies in that very simplicity. Complexity is removed by isolating one narrative and treating it as all encompassing. Parables appeal to artists because craft can encompass such interpretations. Skill shines through where gray does not interfere. In many ways, parables are the direct line to our interior monologue and possibly our purest feelings. Horror movies thrive in this area. Horror revenge and teenage slasher flicks are gore encrusted parables that provide a narrative about proper and improper behavior as well as the resulting punishment for transgressions.

Yet, somehow, I feel as though Clouzot has woven uncertainty into his tale. The struggle is more than driving a camel through the eye of a needle and the narrative moves me powerfully. The difference that distinguishes Clouzot, Spielberg and even Peckinpah is that their characters do have lives that matter beyond being props for a parable, just like the people around us.

What’s it all about?

You’ve Got to Check This Out is a blog series about music, words, and all sorts of artistic matters. It started with an explanation. 24 more to go.

New additions to You’ve Got to Check This Out release regularly. Also, free humor, short works, and poetry post irregularly. Receive notifications on Facebook by friending or following Craig.

Images may be subject to copyright.