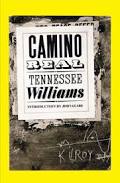

Camino Real

Play written by Tennessee Williams

The stereotypical situation is the parents complaining about how their children take for granted those things that the parents had to do without when they were children. Usually, this involves some theme about sacrifice and making good choices. As a child and a parent, I can’t claim that I’ve been immune to the expectation.

In a sense, a cultural analogy also exists, perhaps without the overriding moral lecture. We don’t quite comprehend a world in which certain works of art never existed. What did the world listen to before rock and roll? Is it possible to grasp the influence of disco and European electronic music (say, like Giorgio Moroder) on current music if you didn’t live through the eras when those styles were ascendant?

For that matter, we don’t really grasp the impact of technology that was omnipresent at our birth. How many people understand the consideration that went onto dragging yourself off the sofa to change the television channel or the record on the turntable? You ended up watching that next crappy show or listening to that filler song on the LP because it was just too much effort to do otherwise.

All art forms arrive on the lives of newborns like avalanches. They started somewhere distant and out of sight, arriving with boulders and pebbles that look solid and feel impenetrable. Moreover, they all originated in a time out of mind.

I cannot truly imagine a world without Benny Goodman, Jane Austen, Michelangelo, Bach, Dante or Picasso. The same can be said of Tennessee Williams. One measure of how large a boulder an artist was (to carry an analogy too far) is whether or not you became familiar with their work before you became familiar with them. For instance, did you know her rhymes or did you know Mother Goose first?

I’ve had the privilege of seeing The Glass Menagerie as a youth as well as seeing its impact on young people of today. A Streetcar Named Desire bred one of our great films and helped cement the career of Marlon Brando. Add to that a list plays adapted to the screen with major casts as well as regular revivals by large and small companies.

Williams cornered the market on the struggle to find yourself through the torment of internal emotions balanced against external pressures. As with so many artists of note that come before us, he provided new grammar for expressing ourselves. Except– by the time I came along, that grammar felt set in stone. His best known work was so well-known that it had always existed. After all, we measure time from our own advent.

Imagine my pleasure to discover that Williams (like many, many other artists) did not view his work as sacrosanct- his path beyond wider exploration. Every now and then, someone revives his play, Camino Real, but that means that you have to read it first. I entertain the illusion that anyone who does actually stumble upon a copy and read the thing feels a sudden desire to see it staged. It’s experimental, which can be a death knell, but it is so in a Williams way with emotional depth and wry humor.

Something reassuring appears when you discover that Shakespeare also wrote Timon of Athens and Cymbeline. Wait, you mean he tried stuff? Really? If he didn’t think his work had to be enshrined in a dark closet at a university, perhaps it does actually have some relevance to now?

What’s it all about?

You’ve Got to Check This Out is a blog series about music, words, and all sorts of artistic matters. It started with an explanation. 76 more to go.

New additions to You’ve Got to Check This Out release regularly. Also, free humor, short works, and poetry post irregularly. Receive notifications on Facebook by friending or following Craig.

Images may be subject to copyright.