Fight the Power

Written by Carlton Ridenhour, Eric Sadler, and Keith Shocklee

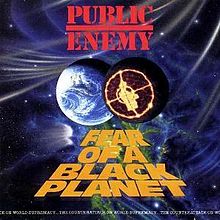

Performed by Public Enemy

She had a single in the dormitory and I happily accompanied her to listen to some music and talk. First, she played some music on her little turntable- something popular from the day, I think. I must have looked dismayed, because she pulled something “cool” out of her small stack of records. Knowing better than to act impressed, I could not admit that she had found something new to me.

Then she hit me with the topic of conversation. Would I be interested in attending her church, specifically the Church of the Latter Day Saints? Yes, you got that right. The Mormons introduced me to rap music. For the record, I attended one service and never saw her or the church again.

My initial reaction to Rapper’s Delight was that it was not very different from all the dance remixes that were popular in the day. Bruce Springsteen did it, and not just on Dancing in the Dark. Georgio Moroder was re-mixing every song in Europe and quite a few others. Then, there was Ethel Merman’s disco album. Why, why, why, indeed.

My point is that The Sugarhill Gang did not seem like a big leap at the time. Record scratching and talking over the music looked like a good idea. In fact, anyone who could recite poetry over music seemed like they might be on to something.

Naturally, every one you met thought they could rap, just as everyone previously had been in a garage band. Sure, this made it seem like the accomplishments of Bachman Turner Overdrive were only a few easy days away.

Of course,

the lyric driven nature of the music lent itself to deeper exploration of topics as well as more extensive detail in stories. A writer must be intrigued.

Then, the great divide began. Like all popular music artists, groups explored issues that spoke to their own experiences as well as would increase their marketability. Even if they had higher aspirations, succumbing to even the outskirts of the music industry acknowledges a desire to appeal to more people than can sit in your driveway. Some artists broke out of their local scene with messages of anger, creating music that had the same energy and force of will as the angriest punk.

For me, the anger and musicality never merited question. Honest emotion well-expressed is essential in art. Add in some consideration of the clarity with which you express yourself and you are making great art in my book.

So, where did a lot of rap lose me (and Public Enemy hold me)? Turns out it’s the same place a lot of pop music has lost me over the years, though I can identify the cause a little more easily in rap music (opera, too, now that I think of it). Artists always face the conflict of the individual and the universal. How do you make your experience into something that your audience can appreciate? With the switch to more extensive story-telling as well as a move away from intricate choruses, my ability to relate to an identifiable emotional core can be limited. Public Enemy always seem able to construct their message in a way that I can find a place of commonality, a place where great art sits.

What’s it all about?

You’ve Got to Check This Out is a blog series about music, words, and all sorts of artistic matters. It started with an explanation. 197 more to go.

New additions to You’ve Got to Check This Out release regularly. Also, free humor, short works, and poetry post irregularly. Receive notifications on Facebook by friending or following Craig.

Images may be subject to copyright.